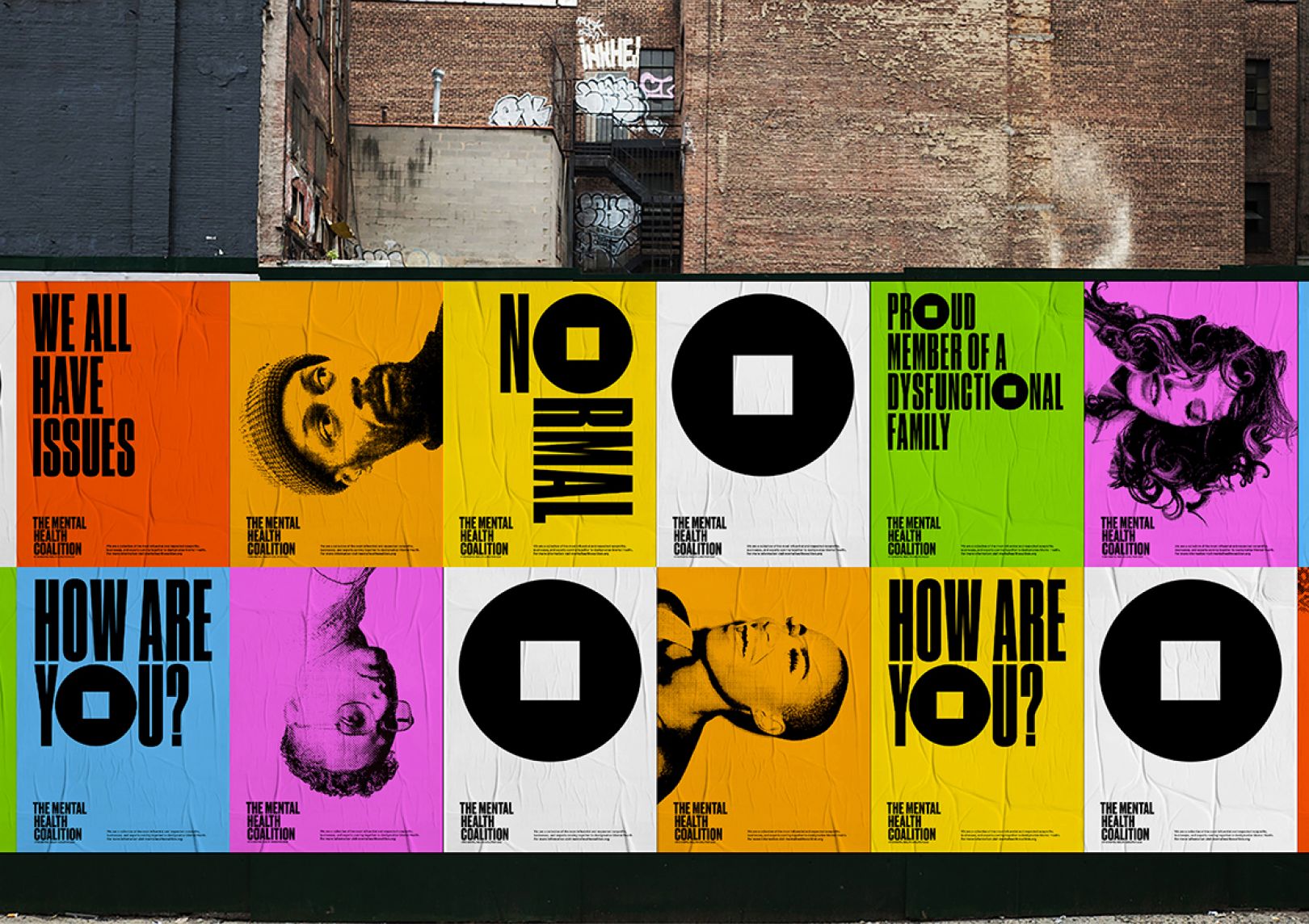

Pentagram pride themselves as being the world’s largest independent design agency. They consist of a team of 24 designers who produce graphics and identity, products and packaging, exhibitions and installations, websites and digital experiences, advertising and communications, and sound and motion.

They claim to be unique in their structure as the only major design studio where the owners of the business are the creators of the work and serve as the primary contact for every client. This allows the designers, whether working individually or as a team, to tackle a design problem with personal commitment, passion and intelligence.

I believe that having pride and passion for the work you produce is so important as a designer because it enables you to be more invested when it comes to solving a problem. If you feel too much as though you’re just a service being paid for by ‘insert brand here’ then the work is much more likely to come out looking stagnant. If you are working hand in hand with the client, it is easier to really get a sense for what the brand are about.

When it comes to brand identity, Pentagram are clearly masters of retaining the core values of a brand at the same time as developing something unique and full of personality. This ability comes from the direct communication between designer and client. The way designers at Pentagram are encouraged to collaborate also allows them to approach a problem from different points of view, allowing for a more creative outcome.

By treating designers as both individuals as well as a collective, each designer at Pentagram seems to be able to work to their own strengths, opinions and values which come together to develop the best solution for the client.

“It was truly about doing the work and not about bureaucracy. The partners are all generous and thoughtful about design and collaboration. It is not like joining some big corporation – it is very personal and human.”

Emily Oberman interviewed by ‘It’s Nice That’

“In theory everyone has the same vote and the same power but there’s things about who’s been there longest, who gets the most press, who brings in certain kinds of projects, who wins the most awards. We each have our values and they’re different. I have seen over eight years discussions where I was definitely on one side and now I see it from another point of view. Maybe we don’t have to take over the world, maybe it’s ok if we lose some projects to Wolff Olins, maybe it’s good that we don’t make as much money because we’ll have more people with suits.”

Luke Hayman interviewed by ‘It’s Nice That’

“If you were practising on your own, you wouldn’t necessarily be provoking yourself to think in [certain] ways. That cyclical reinvention is happening for each partner. The formula, if there is a formula, is in that regeneration.”

Micheal Beirut interviewed by ‘It’s Nice That’

“Students of mine who have gone into big agencies, they’re making changes, they’re not making things. Or they’re making things to make the thing. Or they’re being hired to make the presentation to show the company what it might be like if they do get hired to make the thing!”

Paula Scher interviewed by ‘It’s Nice That’